The Churchill Casebook of Curiosities

Book Three: The Velvet Wraith

Chapter Three: A Visit to Druid’s Heath

Most likely a codSaturday 2nd August 1879: Highbury Hall, Birmingham

Before the dreaded possible intersection of ‘Leopards’ and ‘swimming’ could be resolved I heard a holler from Silas. “Gideon! Are you out here? Mr Van der Valk would like a word!”

“Silas I would like nothing more; however I feel you should know there is something moving in the pond here.”

“Moving? Most likely a cod,” Silas called appearing on the edge of the clearing. “Nothing to be concerned about.”

“How many 6-foot cod have you seen, Silas?”

He scratched his head. “Some? In any case now is not the time—please come with me, it seems we are to embark on a visit to Druid’s Heath.”

Keeping a close eye on the rippling pond I accompanied Silas to the house where Mr Van der Valk handed me a sealed envelope. “Master Chamberlain would see this delivered to Mr Watson, if you please.”

“Watson! That unpleasant fellow. I take it this is Chamberlain’s refusal?”

“I have never seen you pass up an opportunity to cause social anguish, Gideon,” Silas smirked.

“Indeed not; I shall deliver it with relish!”

Blackwood and Silas too had been given duties: Blackwood was instructed to discuss his plans for reviving the struggling mill with the local smithy, an expert in such matters apparently, and Silas had been requested to pick up something at the Inn—a rather mundane task, and one more suited to the staff I would have thought, but Van der Valk insisted it be Silas.

“You’ll find both the collection and Watson at the Nettle & Thorn,” he muttered walking away.

“I can’t help but think we are being arranged to exit the property for the afternoon,” Silas observed with a glance toward the upstairs laboratory.

Saturday 2nd August 1879: Druid’s Heath, Birmingham

Blackwood’s new friends Martin & Roland delivered us to Druid’s Heath safely via cart and horse (I was disappointed to find there were no riding horses), a short ten-minute drive. Despite being a smallish kind of village, there was prodigious black-smithery at the far edge of town that would be our destination after the Nettle & Thorn.

The publican, Mr Barnard, was a friendly sort (aren’t they all?) and settled us in for a pint before getting down to business. Silas’s collection was an assortment of mostly barrels: four of finest bitter, two of vinegar, and another two of used brewer’s yeast (‘useless to us’).

“And can you guess why Mr Chamberlain might think otherwise?” I asked innocently.

“Well ma’am I couldn’t rightly say. The are quite nutritious I suppose?”

“He’s not going to eat them, surely?”

“No Ms Harrow,” Blackwood jumped in, “It would be for the animals.”

“Oh of course!” I exclaimed, somewhat embarrassed.

That settled, I asked Barnard to summon Watson. He arrived before too long looking as sombre as ever. After an appropriate amount of sulking and ignoring the small man’s earnest enquiries as to our presence, I eventually relented. “I have a letter for you, Mr Watson.”

“Mr Chamberlain’s response?”

“I expect so.”

He scanned the letter quickly and nodded. “Then I shall take my leave.”

The poor fellow looked so crestfallen that I decided to forgive his earlier rudeness. At least temporarily. “There now, Mr Watson, surely this is not wholly unexpected news.” He sighed and shrugged. “Well at least you know where you stand. Tell me—why are you so very concerned about this orchid? Surely a single flower cannot be worth such consternation?”

Watson settled slightly, sipping on his tea (he had refused anything stronger). “Unfortunately, madam, this single flower is very much worth the trouble it is causing. It is a long story, but if you have the time?”

At a nod he continued with a tale that mostly matched that which Chamberlain had told us, albeit from quite a different perspective. Watson and co. had engaged in long discussions with one Friar Juan Ignacio Molina, a scientist from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid and the foremost expert on the infamous expedition led by Father Cristobal de Acuña, a Jesuita de Qinto, that unearthed the original Velvet Wraith. After much study Molina had “expressed great concerns, and fears that the orchid may possess dangers that we cannot easily comprehend.”

“What dangers, sir?” I probed. “Chamberlain advised us de Acuña spoke only of the powerful healing properties of the orchid—not danger.”

“Molina was unable—or unwilling—to elaborate. But he convinced me of the truth of his words: there is great peril associated with the Velvet Wraith, and it must be controlled.”

“Are you not a scientist?” Blackwood protested, “And yet the only evidence you can provide is a mystic ‘peril’?”

“Mystic, no. I have never said that,” Watson said sternly. “But a peril indeed.”

“Pharmacological, perhaps?” Silas suggested.

“That is far more likely.”

“And remember Blackwood that we, both men of science, have of late seen much evidence that there is often more to the world than meets the scientific eye.”

Blackwood merely grunted, though the image of Jessica floating, head-spinning, loomed large in all our memories. Let alone our days spent living in reverse.

“Indeed, sir,” Watson nodded, “In any case, we merely wish to be in possession of the plant to ascertain the danger”

Watson’s evasive answers but obvious conviction was all most vexing. After a little more small talk Mr Watson excused himself (allowing me to slip him a card and personal invitation to the Coffee House) and we continued on to the Blacksmith.

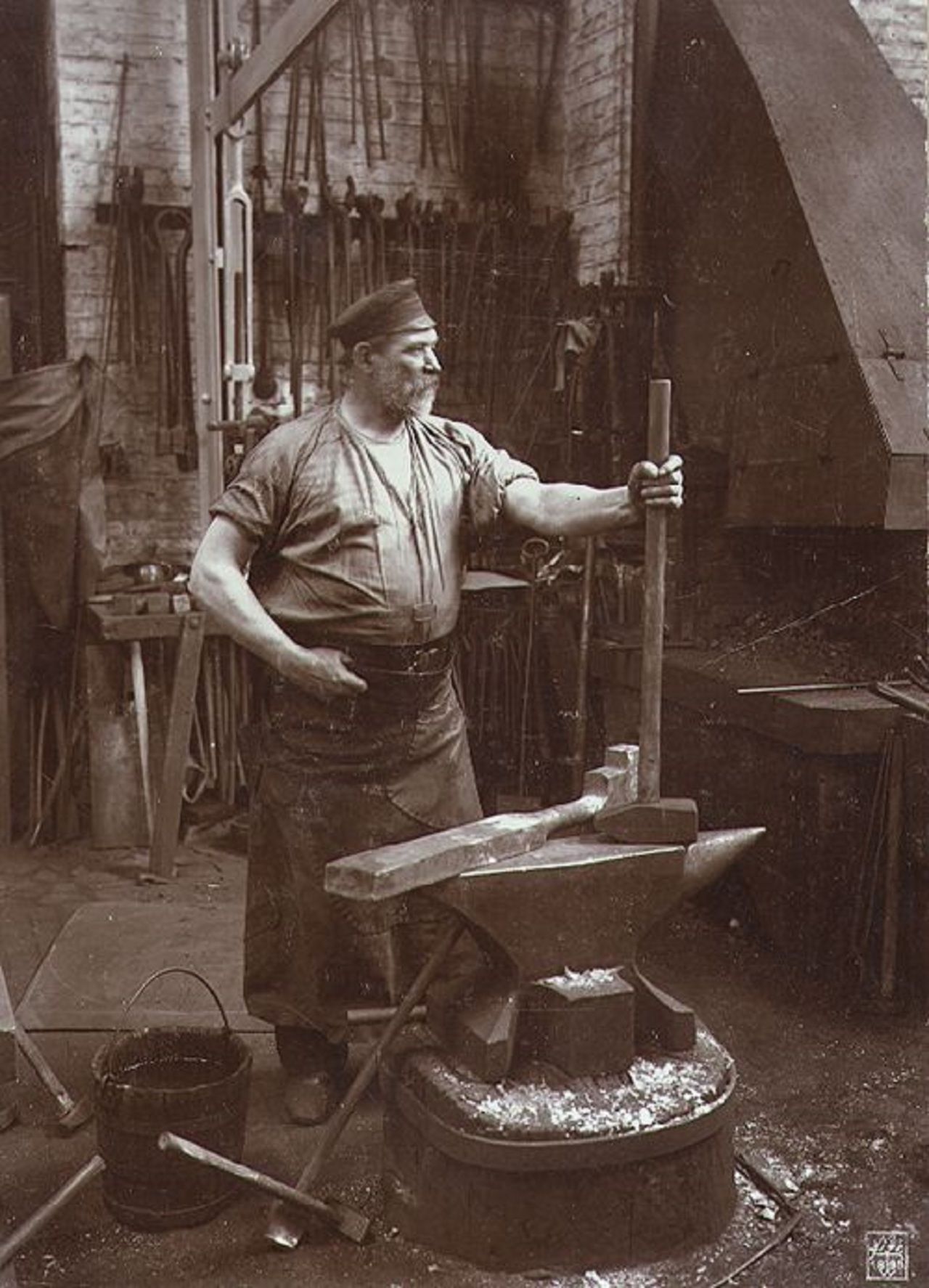

The smithery bellowed smoke that covered the nearby foliage with black. The wheels of industry griding was an unpleasant sight.

Mr Smith

The blacksmith himself was a gruff and plain-spoken fellow, meaning he and Blackwood were well matched. He understood Blackwood’s proposal immediately and before long they were poring over outlines and sketching plans. The man could even do mathematics, much to Blackwood’s delight.

The engine Blackwood had seen came from Druid’s Heath, which was a surprise given the town’s size, until we discovered there was foundry attached to the smithy. Being this close to Birmingham it made some sense, and their expertise was obvious.

It took some ninety minutes (during which both Martin & Roland became rather inebriated; I feared for our trip back to the estate) before a design was settled upon. A second older fellow covered in soot and leather arrived, briefly studied the new drawings and gave a quick nod. “Leave it to me.”

Blackwood couldn’t stop beaming on the rather more haphazard drive back.

Saturday 2nd August 1879: Highbury Hall, Birmingham

We ate (without Chamberlain) before retiring after a quick game of billiards. “You don’t want to scout the house, see if we can find him?” I asked Silas.

“I could bring my hammer?” Blackwood nodded.

“No Gideon, and certainly not, Blackwood! As I have said, that would not be proper—we are his guests, and we should behave as such.”

“You are such a stick in the mud, Silas! But very well: good night, gentlemen.”

“Good night, Gideon,” Silas smiled. “I will just have a few quick nightcaps.”

Not an hour later there came a pounding on my door. “Pssst. Gideon!”

“Silas?”

“Yes! Are you ready to explore?”

“Am I…no! What on earth do you mean creeping around like this, Silas?”

“Oh come on Gideon, you know you want to!”

“You are quite impossible!” I scowled, but climbed out of bed and wrapped myself in a gown. I jerked the door open to find Dr Hawthorne with whisky almost leaking out of his eyeballs. “I should have known,” I sighed. “Let’s get Blackwood.”

Blackwood opened his door still fully dressed. “Oh now you want my hammer?” he grinned.

We proceeded to venture around the second floor, finding nothing of interest—though Blackwood and Silas were thrilled by my story of the mandrill when I showed (and warned them of) the gantry. The first floor was the same: no sign of Chamberlain anywhere, and no hidden rooms or passages.

The thrill of an illicit adventure wore off faster than I expected; it had been a long day, I realised, woken at dawn and still going at midnight. “Gentlemen I have had quite enough and will retire,” I announced.

“But we haven’t searched the lower floor,” Blackwood said, hoisting his hammer.

“Gideon’s right, Blackwood,” Silas yawned, “It’s late and we can venture down there tomorrow night if we don’t beforehand.”

We withdrew to our rooms and I collapsed back into my bed. I reflected that if there were an omniscient force–a ‘god’ or ‘master of games’—watching over us they would be somewhat bemused with the outcomes of our day: no surprises, no discoveries, and a surfeit of faffing. But such was life.

Just before drifting off to sleep there was one final interruption: another scream, this time accompanied by a troubling gurgling, slurping sound.

I rolled over, pulled a pillow over my head, and ignored it.