The Churchill Casebook of Curiosities

Book Three: The Velvet Wraith

Chapter Five: A Stranger at the Gates

If they were lions we would both be deadSunday 3nd August 1879: Highbury Hall, Birmingham

“A man you say? Should we summon Van der Valk?” I said to Jack as he peered at the solitary figure standing at the gates.

Jack, being Jack, didn’t answer, instead he charged off to meet the stranger. I followed, protesting all the while that this was not quite proper.

It was an older gentleman with an old-fashioned dark-haired wig (or at least I hope it was a wig) who peered through the bars.

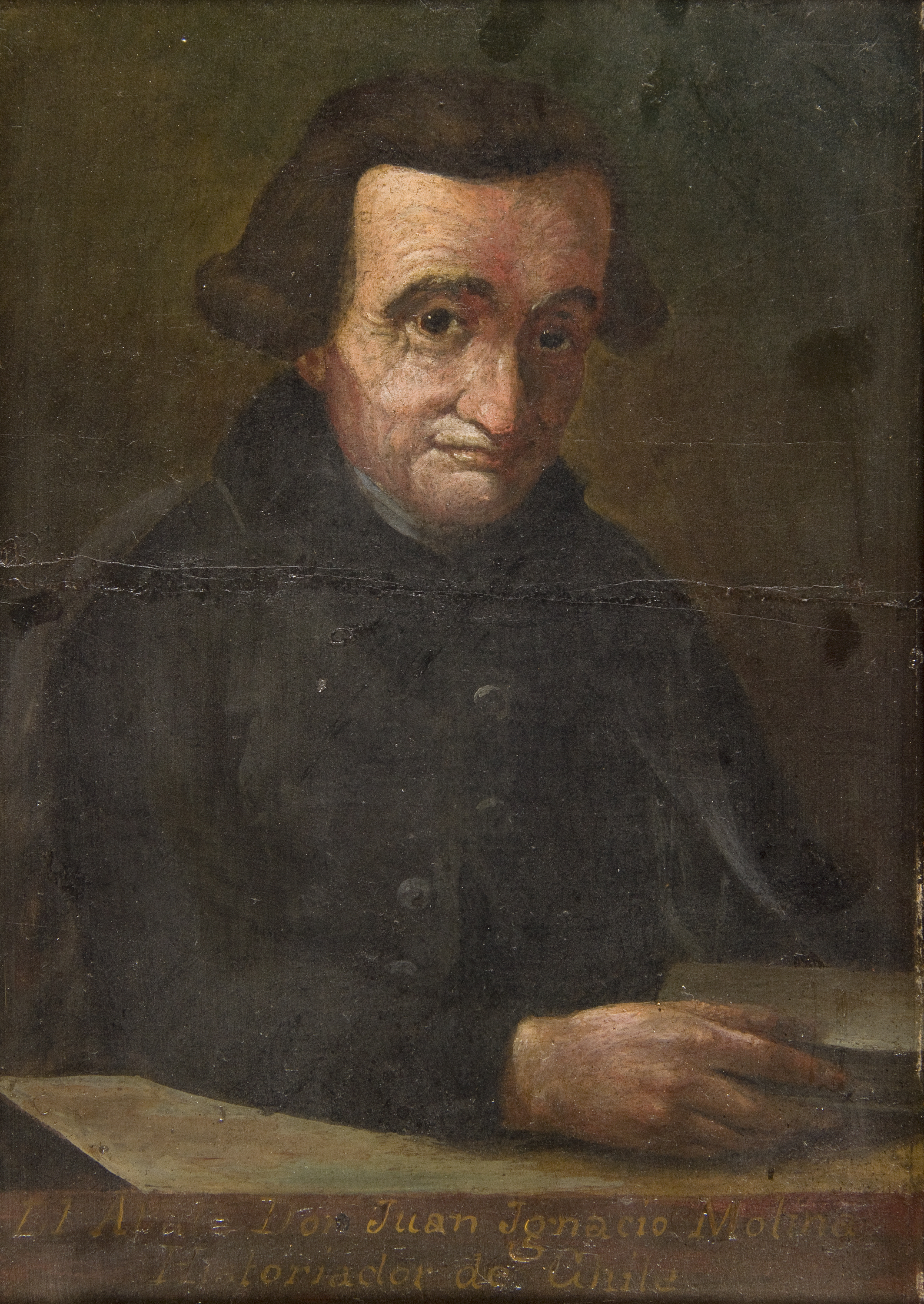

Friar Juan Ignacio Molina

He announced he was here to see the Master and as he negotiated through Jack’s customary confusion (“My master? I don’t have one?") I detected an unusual accent: Spanish? Portuguese? His next words gave me the answer:

“My name is Dr Molina, and I would like to see Mr Watson if I may?”

Molina! Could it be? “Sir it is a pleasure to meet you. I am Ms Gideon Harrow, and I must ask: are you the famous Dr Molina? Mr Watson had a very high opinion of your work.”

“You have me at a disadvantage madam,” Molina bowed. It was him! He went on to insist on seeing Watson, and curiously would not take a step inside the gate once I had surreptitiously unlocked it. “It is only that Mr Watson has been missing from his abode in the town, and yet he has left all of his belongings. The publican fears he may have left without paying his dues, though that is not the Mr Watson I know.”

I shot a sharp glance to Jack at this; the evidence was mounting that Mr Watson really had met his demise. “Please come and meet Mr Chamberlain, in Mr Watson’s absence,” I begged. “I am sure he will be most interested in meeting you.”

Molina paled at this. “I know Chamberlain only by reputation, and I would rather keep my distance, madam.” When pressed as to why he continued: “Chamberlain is dangerous.”

“What do you mean, Dr Molina? In what way?”

“Because of the orchid, madam. His intimate knowledge and research makes him a danger both to himself and those near him. Indeed I fear not only for Watson, but for you also.

Blackwood and I both were stunned by this, but before we could press him any further he bowed again. “I will be staying at the Nettle & Thorn in Druid’s Heath for a few days, hoping for Mr Watson’s return. Please come and see me if you would like to speak further.”

With that he walked away, sliding the gate latch shut as he did.

“We must tell Silas!” I urged as we turned back toward the manor. And stopped in our tracks.

Not one but two leopards were stalking their way toward us, eyes locked on what to them was no doubt tasty meat. One approached from the left, the other the right, trapping we victims in a pincer.

“Jack! Run!” I cried, staggering back into the now locked gate.

“Madam calm yourself,” Jack said softly, standing stock still. How could he be so calm! He suddenly reared up to what felt double his size and spooked the nearest leopard which halted its advance. I felt my heart racing and blood rising as I frantically tried to get the gate open. Without warning my mind went blank and, to my eternal shame, fainted!

Jack roused me moments later. “Wake up, Madam, it is perfectly safe.”

I sat up, head woozy, to see one leopard sitting on its haunches only metres away, licking a paw. The other still stood watching idly, more curious than hungry. Jack lifted me to my feet. “Madam please walk with me, calmly and confidently. No sudden movements and all will be well.”

I did as ordered, and soon we were making our way back past the water feature (which one of the leopards drank from with obvious satisfaction) toward the house. I recalled Van der Valk’s earlier wisdom: “Don’t give them anything to chase”, and it seemed Jack too knew that truth. Feeling rather bolstered, I stopped and turned to study the leopards. “Which one is Tabitha and which Khan, do you think?”

“I would have to get closer to be sure,” Jack smiled.

“Please don’t! But they are quite magnificent. Amazing animals; thank you, Jack, for first bringing me tea and now saving my life.”

“If they were lions we would both be dead,” Jack said matter-of-factly. I quickened my pace toward the house.

Lunch was ready when we finally arrived back, or should I say several hours overdue, much to Mrs Macbeth’s displeasure. “Let’s keep Molina’s visit from Chamberlain for the time being,” I whispered to a nod from Jack.

We were joined by Chamberlain and Silas before long. When we mentioned our encounter with the leopards he laughed. “There is a third you know—Sasha. He’s rather less friendly and harder to spot: a black coat, most unusual.” Silas filled us in on the experiments, declaring they were going well but it was too early to say anything definitive.

I tried to try and catch Chamberlain out again as we discussed the orchid more. “Now that you have disposed of Watson, what will you do next?” I asked innocently.

“Disposed?” he said without a blink or pause.

“Well I presume that it what your letter to him advised? That he should no get his hopes up for access to the Velvet Wraith?”

“Quite so, madam.” If he was a murderer he had the best poker face I had yet encountered. I decided to take a fresh tack: I wanted him to meet Molina, but was certain that invitation would have to come from Chamberlain himself—his ego was too powerful to admit a stranger or someone who might question his motives.

“Excuse me for being blunt, Sir, but would it not be in your best interests to seek a second, someone who could verify your claims? After all is that not what science is, proof and further proof?”

“You’re talking about peer review,” Silas nodded. “Which is why I am here, right Potters?”

“Just so, Spikey, just so!”

“Silas really,” I frowned. “You have said yourself that you are no botanist, and indeed feel rather on the backfoot with all this orchid tomfoolery! Chamberlain needs an expert, someone his near equal in expertise.”

“Madam I have stated already that there is no need. Once the world sees what I have discovered the truth will be there for all who seek to find it.”

“But Dr Chamberlain what is the harm? Would your claims not be all the greater for being celebrated and corroborated by your actual peers,” I said with a glance to a scowling Silas. He would forgive me later, I hoped.

“Madam you are formidable. But I refuse: they are not to be trusted. Not a one of them.”

After lunch we excused ourself from Chamberlain and we filled Silas in on Molina.

“He believes Watson is missing, so it may be you are quite right that he is in fact dead,” I said.

Much to my disgruntlement Silas had apparently changed his tune in the intervening hours. “I have given it some thought, and seeing how your recent wordplay had no effect made me more certain that Joseph may not be the murderer we feared. It now seems more likely that Mr Watson returned and was attacked by one of your leopards.”

“But Silas we saw signs of struggle in the greenhouse, just like by the pond!”

“Then perhaps it was the mandrill instead. And Van der Valk and the farmhands had to clean up the mess. Covering up is not the same as murdering, Gideon.”

I had finally come around and now he was proposing some other explanation. Impossible man. “Silas you vex me greatly. Surely you cannot be saying that Chamberlain’s behaviour is ‘normal’. You directly accused him of hiding something!”

Silas sighed. “Potters hasn’t changed; an arrogant young man is now an arrogant older man. That does not make him a killer.”

“Let’s examine the facts, shall we Doctor,” I snapped. “Chamberlain is doing his experiments, aided and abetted by your good self. Trying to make more orchids, if I understand correctly, which you claim is perfectly safe.”

“He is attempting to artificially propagate the orchid, yes,” Silas said patiently. “And as far as I can see there is no sign of danger, nor anything dangerous about his process.”

“Very well. Now, on the opposing side we have Mr Watson and Dr Molina, both of whom take quite the opposite position: that the work Chamberlain is engaged in is not only dangerous, it is deadly, and deadly to anyone that comes close. That is quite the different understanding, and I think we should treat it seriously.”

Silas nodded, thoughtfully. “Of course we should. Let us visit Molina.”

At the Nettle & Thorn Mr Barnard summoned Molina and we settled into a quiet corner after introducing Silas.

“Dr Hawthorne you are a trusted colleague of Dr Chamberlain?” Molina started, cutting straight to the chase.

“An old acquaintance would be more accurate,” Silas said.

“And you are working with him on his project? How is your friend, would you say?”

“He is as consistent in character as he was where we were closer.”

“That is good.”

“Dr Molina, what would you expect Dr Chamberlain to be like, given your fears?” I asked.

“I am not sure, but I will tell you a story,” Molina said. The tale he proceeded to tell was quite something.

His correspondence with Watson centred on the story of the Cattleya fantasma terciopelo, the Spanish name for the Velvet Wraith, and Father Cristobal de Acuña’s infamous 1639 expedition.

De Acuña’s party travelled up the Napo River, a tributary of the Amazon rising in the Ecuadorian highlands of Perdida Tepui, where it fell prey to many perils: disease, starvation, animal attacks, and eventually de Acuña’s own madness. “He was nursed back to health with the administration of the nectar of the orchid by the Zápara tribe,” Molina explained.

“The Zápara were the same tribe Chamberlain claimed to have saved him,” I observed quietly.

He went on to reiterate what Watson had told us days earlier: that the expedition returned to Spain but the orchid specimen was dead on arrival. It was studied in great detail by the Universidad Complutense de Madrid (“the finest and oldest university in Madrid”) with de Acuña’s diaries forming the main body of knowledge. He later published his definitive memoir, Nuevo Descubrimiento del gran rio de las Amazonas.

“The Zápara called the orchid Yura Wasi Yuyay, meaning either ‘The Plant of One’s Dreams’ or perhaps more ominously ‘The Plant That Takes Root in Your Thought’. Your own Orchid Society has tentatively assigned the name Cattleya larua arcanus to the plant in question: Cattleya ‘hidden ghost’.”

Silas, who had remained silent during Molina’s exposition, was fast losing patience. “Dr we have heard nothing of concern, in fact, truth be told, we have heard only that the orchid has healing powers that cured de Acuña or his physical and mental ailments, and which Chamberlain claims is doing the same for his malaria. Why would we want to stop that? Frankly we would all benefit from more candour: what precisely you are warning of?”

Molina nodded grimly. “I am not an orchid expert; I am an expert in the Spanish expeditions, chair of Botanical Historiography of the New World. There was another more qualified man that followed in de Acuña’s footsteps: Friar Juan Pablo Montoya. in 1650 he visited the various tribes that de Acuña had encountered, including most particularly the Kayapo people.

The Kayapo told Montoya of their ongoing conflicts with the Zápara; they fought them whenever and wherever they met, which was not often but often enough. “All tribes shunned the Zápara, driving them back into the highlands and the plateau from which then came. And when they came, they came in swarms: fighting without fear or emotion, of a single purpose without individuality or fear. The Kayapo called them the Pipiyollin Hakah as a result, a phrase meaning ‘bee people’.”

“Montoya’s findings were recorded in his own work, Un estudio de las tribus indígenas del valle del Napo. And those findings are the foundation of our concerns.”

Silas shook his head. “This is not clarity, Dr Molina. The clear and present danger you warn of is based on a second hand account of a first hand account. Two expeditions with a tenuous connection at best with Chamberlain’s discovery—one which describes a very efficacious effect, quite contrary to your fears. Based on that the orchid is not a danger to all and sundry as you claim. And these accounts are ancient history now—how old is de Acuña’s work?”

“Two hundred and fifty years,” Molina conceded.

“So a reformation document—”

“The bible is older than that and we take that rather seriously, Silas,” I interrupted.

“Don’t get me started,” Silas snapped. “As I was saying, a reformation document suggests a fanciful and barely explained danger related to dead plant that was returned centuries ago. And you wish us to apply that same danger to Chamberlain’s orchid which, from all available scientific evidence, has no dangerous properties whatsoever. There is no clear link to this flower, and at worst we can imagine is it acting as a psychotropic or laudanum. You can surely understand my scepticism, Doctor.”

“Like opium,” Blackwood added thoughtfully.

I was somewhat taken aback by Silas’s directness; it was almost rude. And I had quite a different take. “Silas, no. It is not an opiate or laudanum that is being described. You well know my experience with both, and what Dr Molina describes is markedly different. Those are solo effect, individual interruptions to reality. This is a shared, communal experience, something that turns hundreds of individuals into automatons. They described them as bees, mindless drones working as one.”

“Precisely,” Molina nodded. “Whether infected or imbibed, their actions were driven by the wants of the plant.”

Silas shot him a look, surprised to see he was earnest, almost relieved, that someone believed him.

“He is saying the plant was controlling their minds, Silas. And could be controlling Chamberlain’s mind.”

Molina stood. “I will take my leave, but please consider my words. I come here only, only to protect those that may suffer from the unfortunate discovery of something that should have remained forever hidden.”

We sat exhausted and in silence. I could see Silas was still vexed, but also that the final words had planted a seed (ahem) of doubt. “You know, Gideon, Chamberlain is right. You are formidable.”

I blushed appropriately.

“If we have learned anything in our recent adventures is that there is more than meets the scientific mind at play in this world. So a plant that controls minds? Why not.”

As we went to leave I placed several coins on the counter and nodded to Mr Barnard. “That should be enough to cover Mr Watson’s rent, I trust?”

“Indeed it does, thank you Madam. Does that mean Mr Watson is not returning?”

“Oh! No!” Blackwood jumped in. “He is, it’s just…we will take his belongings with us. We expect him to join us shortly.”

Barnard raised an eyebrow but nodded. “Back to Highbury Hall then?”

“Exactly—if you can show us to his room we will take care of it.”

“Really Mr Blackwood could not Mr Barnard send his things, I am rather weary?”

“No, no, we should take care of it,” Blackwood insisted. I could not fathom why. Men!

“Mabel! Key to number three if you please!”

We collected Mr Watson’s belongings, a rather grim affair when I considered his probable demise. Silas and Jack obviously hoped to find something of interest despite my assurance it was a wasted of time; a thief knows…

…but sometimes they don’t.

Silas was clearing the desk when he found the envelope I had delivered to him. “It’s just Chamberlain’s no doubt quite rude dismissal,” I yawned.

Silas peeled it open none the less, an astonished look washing over his face as he read. “My god! Chamberlain wrote to invite Watson to view the orchid!! He apologies for his rudeness and hopes to make things right, blah blah, ‘please come at your earliest convenience, tonight if that would be amenable'!”

We were stunned. “But…the letter…” I stammered. “The letter was an invitation to his death!”

“The evidence was waiting for us all this time,” Silas groaned. “Why didn’t you take a peek before delivering it, Gideon, you could have saved Watson!”

I could see Silas was joking, but it was a black humour indeed.

“So Chamberlain was lying after all,” Jack scowled.

“Not Chamberlain,” I gasped, revelation dawning. “The Velvet Wraith! The plant instructed him to summon Watson because Watson was a threat to its existence. Chamberlain really does have no idea! Silas—we have to destroy the samples!”

“We have to destroy the samples,” Silas concurred.

“And the distribution pipes,” Jack said firmly.

“Let’s get to work, gentlemen!”